Written By: Team Pharmacally (Shreya Bendsure BPharm, Sheetal Barbade BPharm, Vikas Londhe MPharm-Phrmacology)

Medically Reviewed By: Dr. Htet Wai Moe, MBBS, MD-Pharmacology

PhD-Pharmacology

Defence Services Medical Research Centre, Naypyitaw, Myanmar

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder marked by memory loss, cognitive decline and behavioural changes. Its neuropathology includes extracellular amyloid‑β (Aβ) plaques, intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyper‑phosphorylated tau protein, synaptic and axonal degeneration, inflammation and neuronal death. With Alzheimer’s disease affecting more than 50 million people worldwide and cases expected to triple by 2050, novel preventive strategies are urgently needed. Despite extensive research, therapies that slow or prevent AD remain limited. Recently attention has shifted toward repositioning existing compounds with pleiotropic actions. Lithium, a simple alkali metal long used as a mood stabilizer, has emerged as a candidate because it can modulate multiple cellular pathways implicated in AD. Epidemiological studies, pre‑clinical experiments and small clinical trials suggest lithium may protect the brain and even modify the course of AD. In 2025, a Nature study revealed that lithium is not just a pharmacological agent but an endogenous element whose deficiency may be an early feature of Alzheimer’s pathology. This article discusses historical and recent evidence on lithium’s relationship with AD.

Lithium as a trace element to manage mood disorders

Lithium (Li) is the lightest solid element. Nutrition guidelines suggest intake below 1 mg/day for a 70‑kg adult. Since the mid‑20th century lithium carbonate has been the benchmark therapy for bipolar disorder, with therapeutic serum concentrations of 0.7–1.2 mmol/L (300–2700 mg/day). These doses require monitoring because lithium has a narrow therapeutic window; serum levels above 1.5 mmol/L produce toxicity (fatigue, tremor, nausea, diarrhoea and confusion) and levels above 2.5 mmol/L may cause seizures, arrhythmia and coma. Lithium also crosses the placenta and is secreted in breast milk, highlighting the need for dose adjustments during pregnancy.

Observational Evidence: lithium in drinking water and dementia risk

Public health studies provide interesting evidences that very low lithium exposures may be associated with lower dementia rates. A systematic review of ecological studies found that trace lithium levels in drinking water (0.002–0.056 mg l⁻¹) were associated with lower incidence and mortality from dementia, whereas concentrations below 0.002 mg l⁻¹ offered no benefit. Another review noted that low‑level lithium exposure through drinking water correlated with increased human lifespan and reduced rates of depression and dementia. In some cohort studies the protective effect was stronger in women, but results varied between geographic regions. Such epidemiological data cannot prove causality but hint that micro‑quantities of lithium may influence brain ageing. These findings inspired pilot trials where micro‑dose lithium slowed cognitive decline and reduced cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) phospho‑tau (P‑tau) levels in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Thus, observational evidence paved the way for mechanistic research and clinical testing.

Discovery of brain lithium deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease

Key findings from the 2025 Nature study

A landmark 2025 paper in Nature investigated endogenous metals in post‑mortem human brains and found that lithium is the only metal significantly reduced in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with MCI and AD. The reduction was specific to the prefrontal cortex; lithium levels remained normal in the cerebellum. Mass‑spectrometry mapping revealed lithium sequestered within Aβ plaques, which created local depletion in plaque‑free cortical areas. In mice engineered to accumulate Aβ, a low‑lithium diet (~50 % reduction) accelerated Aβ deposition, tau phosphorylation, microglial activation, synapse and myelin loss and produced cognitive decline. These effects were partly mediated by over‑activation of glycogen synthase kinase‑3β (GSK‑3β), a key enzyme in tau phosphorylation. Replenishing cortical lithium with an “amyloid‑evading” salt, lithium orotate, prevented pathological changes and restored memory in mice without causing systemic toxicity. The study suggests that maintaining endogenous lithium levels is essential for brain homeostasis and that lithium deficiency may be an early event in AD pathogenesis.

However, the evidence is based on preclinical experiments and postmortem analyses, which demonstrate a biological correlation rather than direct causal proof. If confirmed, this could open the door to preventive lithium supplementation strategies tailored to individuals with early cognitive impairment.

Why lithium Orotate?

Lithium carbonate, the standard psychiatric formulation, binds strongly to Aβ aggregates and is rapidly sequestered into plaques, limiting its availability in surrounding tissue. Lithium orotate is an organic lithium salt that does not interact as strongly with amyloid deposits and therefore maintains extracellular lithium levels at micro‑molar concentrations. In mouse models, lithium orotate delivered at one‑thousandth the dose of lithium carbonate replenished cortical lithium, reversed plaque and tau pathology, reduced microglial activation and synaptic loss and restored memory. These results have sparked interest in developing micro-dose lithium formulations that are both brain-penetrant and safe.

How does lithium protect the brain? Molecular mechanisms

Overview of lithium’s multi‑targeted actions

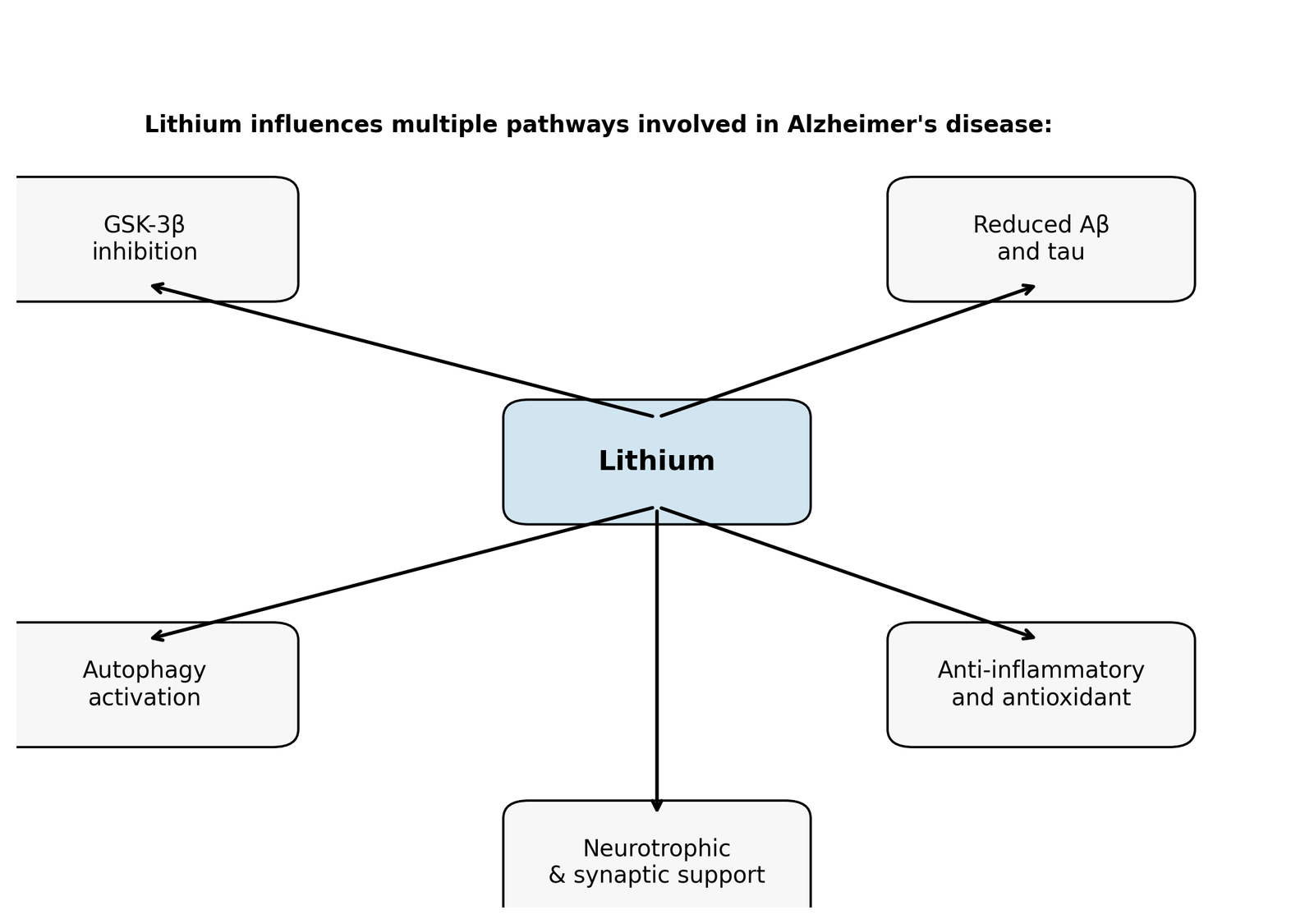

Lithium is often labelled a “dirty” drug because it interacts with multiple intracellular pathways. This non-selectivity may be advantageous in a multifactorial disease like AD. Two primary molecular targets are inositol monophosphatase (IMPase) and GSK‑3β. By inhibiting these enzymes, lithium influences autophagy, cytoskeletal dynamics, gene expression, energy metabolism, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Key mechanisms relevant to AD are summarized below and illustrated in Figure 1.

Inhibition of GSK‑3β and modulation of Wnt/β‑catenin signalling

GSK‑3β is a constitutively active kinase implicated in tau phosphorylation and Aβ generation. Lithium inhibits GSK‑3β directly by competing with Mg²⁺ at its catalytic site and indirectly by promoting inhibitory phosphorylation (Ser‑9) via Akt signaling. This inhibition activates the Wnt/β‑catenin pathway; β‑catenin accumulates in the nucleus and down‑regulates genes such as BACE1 (β‑secretase), thereby reducing Aβ production. GSK‑3β inhibition also attenuates pro‑inflammatory transcription factors NF‑κB and STAT‑3 and enhances antioxidant response via the NRF2/HO‑1 pathway.

Suppression of amyloid‑β pathology

Lithium reduces Aβ accumulation through multiple routes. By inhibiting GSK‑3β it decreases phosphorylation of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and diminishes BACE1 and γ‑secretase activities, leading to less Aβ generation. Lithium also promotes the non‑amyloidogenic cleavage pathway by enhancing α‑secretase activity and facilitates Aβ clearance across the blood–brain barrier by up‑regulating low‑density lipoprotein receptor‑related protein 1 (LRP1) and cerebrospinal fluid bulk flow. In transgenic mice, chronic lithium treatment lowered soluble and insoluble Aβ, reduced plaque burden and improved cognitive performance.

Modulation of tau phosphorylation and aggregation

Tau hyper‑phosphorylation destabilises microtubules and drives neurofibrillary tangle formation. Lithium’s inhibition of GSK‑3β directly reduces tau phosphorylation. It also promotes tau binding to microtubules, lowers tau mRNA expression and enhances ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. In various AD models, lithium reduced insoluble tau aggregates and improved axonal transport, but intervention may need to occur before extensive tangle formation.

Activation of autophagy and clearance pathways

Autophagic clearance of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles declines with age and in AD. Lithium stimulates autophagy through an mTOR‑independent mechanism by inhibiting IMPase and inositol polyphosphate phosphatase, which lowers inositol and IP₃/DAG levels. Enhanced autophagy facilitates removal of Aβ, P‑tau and dysfunctional mitochondria, and combining lithium with rapamycin (an mTOR inhibitor) further augments autophagic flux.

Anti‑inflammatory and anti‑oxidant actions

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of AD. Lithium suppresses pro‑inflammatory microglial and astrocytic activation, lowering cytokines such as IL‑1β, TNF‑α and IL‑6. GSK‑3β inhibition dampens NF‑κB and STAT‑3 signaling and increases the NRF2/HO‑1 axis, boosting antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase and catalase. Lithium also stabilizes mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC‑1α and reduces reactive oxygen species production. These effects support neuronal survival and energy metabolism while preventing apoptosis, as lithium increases anti‑apoptotic Bcl‑2 and decreases pro‑apoptotic Bax.

Neurotrophic signaling and synaptic plasticity

Lithium promotes neurogenesis and synaptic maintenance by activating the PI3K/Akt/CREB pathway, leading to increased expression of brain‑derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF supports synaptic plasticity, dendritic growth and learning. Lithium also regulates cholinergic and glucose metabolism maintains telomere length and may reverse age‑related decline in hippocampal neurogenesis.

Micro‑dose and novel lithium formulations

Micro‑dose lithium and NP03

Traditional lithium therapy uses millimolar concentrations with risk of toxicity. Animal studies demonstrate that sub‑therapeutic doses achieve neuroprotection. For example, micro‑dose lithium NP03 (0.2 mmol kg⁻¹ day⁻¹) administered for 8–12 weeks in APP transgenic rats significantly reduced BACE1 activity, decreased soluble and insoluble Aβ, prevented cholinergic bouton loss and improved memory. In senescence‑accelerated SAMP‑8 mice, similar dosing suppressed inflammatory cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α) and increased synaptophysin, a synaptic marker. These benefits occurred at doses hundreds of times lower than those used for mood disorders, indicating a wide therapeutic window.

NP03 is a proprietary nano‑encapsulated lithium citrate (commercially known as NanoLithium®) that uses Aonys® technology to attach lithium to high‑density lipoproteins (HDL). After absorption through the oral mucosa, the HDL‑bound nanoparticles cross the blood–brain barrier via scavenger receptor class B1, releasing lithium directly into neurons. This targeted delivery allows pharmacologically active concentrations at lower doses, reducing systemic toxicity. Pre‑clinical studies showed that NP03 (≈40 µg Li kg⁻¹) inhibited GSK‑3β, lowered BACE1, reduced amyloid levels, enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity and improved memory function. NP03 also decreased markers of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress and was effective even when given after plaque formation. A multi‑Centre double‑blind clinical trial is underway to assess the safety and efficacy of NP03 in people with mild‑to‑severe AD; participants will receive NP03 or placebo during a 12‑week double‑blind phase followed by a 36‑week open‑label phase and will be monitored using biomarkers, imaging and cognitive testing.

Lithium orotate and other salts

Lithium orotate, used in the 2025 Nature study, consists of lithium bound to orotic acid. Orotic acid is abundant in dairy products and may facilitate lithium transport across membranes. In AD mouse models, micro‑dose lithium orotate reversed Aβ and tau pathologies and improved memory performance in animal models at roughly 1/1 000th of the lithium carbonate dose. Because it is not readily sequestered into Aβ plaques, lithium orotate maintains bioavailable brain lithium at extremely low systemic concentrations. Pilot human studies of lithium orotate have not yet been published, and safety profiles remain under investigation.

Ionic cocrystal AL001

AL001 is a novel ionic co‑crystal combining lithium salicylate with proline to form a stable structure. Pre‑clinical studies showed that AL001 preserved associative memory and reduced irritability without affecting body weight or organ growth. A phase 1/2a randomized clinical trial is assessing the safety and maximum tolerated dose of AL001 in patients with mild‑to‑moderate AD and healthy adults. Another two‑year trial (LATTICE) is comparing lithium carbonate to placebo in 80 older adults with MCI, measuring cognition, biomarkers and brain imaging.

Evidence from human studies

While pre‑clinical data are compelling, human evidence is still emerging. Small randomized trials in the late 2000s reported that AD patients receiving lithium carbonate for 10 weeks showed improved cognitive scores and increased serum BDNF compared with placebo. Two randomised trials in patients with amnestic MCI found that chronic lithium treatment achieving serum levels of 0.25–0.5 mmol L⁻¹ (sub‑therapeutic for mood disorders) slowed cognitive decline, decreased CSF P‑tau and increased Aβ_{1–42} levels. A longitudinal follow‑up 13 years later revealed that participants originally treated with lithium had better cognitive and functional outcomes than matched controls. However, other trials found no cognitive benefit from short‑term lithium therapy despite achieving target serum levels. Variability may reflect differences in dose, treatment duration, disease stage and individual sensitivity. There are also anecdotal reports of lithium reducing agitation in AD patients, but larger studies are needed.

Micro‑dose lithium supplements have gained attention due to their safety; in a small trial using 300 µg lithium per day, cognitive decline slowed and mood improved in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Sub‑therapeutic serum levels (0.25–0.5 mmol L⁻¹) appear to modulate biomarkers without causing toxicity, but further randomised trials are required to validate efficacy and long‑term safety. Importantly, no study yet demonstrates disease reversal in humans; the promising mouse data serve as a proof‑of‑principle that should not be extrapolated directly to clinical practice.

Safety considerations and challenges

Lithium’s therapeutic index is narrow; chronic high doses can damage kidneys and thyroid and cause tremor, cognitive dulling, arrhythmia and birth defects. In contrast, micro‑dose formulations deliver lithium at concentrations hundreds of times lower than psychiatric doses. Animal studies and early human trials suggest that such doses are safe and may even confer benefits but long‑term effects remain unknown. Patients taking lithium should undergo regular monitoring of serum levels, renal function and thyroid function, and pregnant women require careful dose adjustments. The heterogeneity of AD means that lithium might benefit some individuals (e.g., those with early Aβ pathology and low lithium levels) more than others. Additionally, interactions with other medications, dehydration and salt intake can affect lithium levels. Until larger trials are completed, self‑medication with lithium supplements is not recommended; decisions should be made under medical supervision.

Conclusion and future directions

Lithium has travelled a remarkable journey from a simple mood stabilizer to a potential disease‑modifying agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence from ecological studies, animal models and small clinical trials suggests that low‑level lithium supports brain health by simultaneously reducing Aβ generation, inhibiting tau phosphorylation, enhancing autophagy, suppressing neuroinflammation, stabilizing mitochondria and promoting neurogenesis. The 2025 discovery that endogenous lithium deficiency occurs early in AD and that replenishing it prevents pathology in mice adds urgency to this research. New formulations such as lithium orotate, nanolithium (NP03) and ionic co‑crystals seek to deliver lithium to the brain at micro‑doses while minimizing toxicity. Early human trials using sub‑therapeutic doses show promising cognitive benefits, yet results are mixed and larger, longer studies are ongoing. Future work should clarify optimal dosing, identify biomarkers (such as brain lithium levels) to select candidates for therapy and assess long‑term safety. If confirmed in large-scale trials, micro-dose lithium could become part of a multi-pronged approach to delay Alzheimer’s progression. Until then, lithium remains an experimental adjunct rather than an approved therapy.

In summary, the report highlights that lithium is more than just a mood stabilizer; it is a trace element whose deficiency may precede and drive Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiological studies link higher lithium levels in drinking water to reduced dementia risk, and the 2025 Nature study found lithium depletion specifically in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. In mouse models, this deficiency accelerated amyloid‑β deposition, tau hyper phosphorylation and neuroinflammation, while replenishment with lithium orotate improved cognitive performance.

The report also explains how lithium exerts multi-targeted neuroprotective actions by inhibiting GSK‑3β, reducing amyloid‑β production, suppressing tau phosphorylation, stimulating autophagy and dampening inflammatory pathways. Novel formulations such as nano‑encapsulated lithium (NP03) and ionic co‑crystal AL001 are discussed; these deliver micro‑doses that cross the blood–brain barrier, demonstrating efficacy in preclinical models and entering early-phase clinical trials. While small human trials with low-dose lithium show promising cognitive benefits, the report emphasizes that larger, long-term studies are needed to confirm safety and efficacy.

Ultimately “from mood stabilizer to neuroprotector, lithium’s story reminds us that sometimes the smallest elements can have the biggest impact”.

References

Aron, L., Ngian, Z.K., Qiu, C. et al. Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 645, 712–721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09335-x

Radanovic M, Singulani MP, De Paula VJR, Talib LL, Forlenza OV. An Overview of the Effects of Lithium on Alzheimer’s Disease: A Historical Perspective. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025 Apr 5; 18(4):532. Doi: 10.3390/ph18040532. PMID: 40283967; PMCID: PMC12030194.

Fraiha-Pegado J, de Paula VJR, Alotaibi T, Forlenza O, Hajek T. Trace lithium levels in drinking water and risk of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2024 Aug 30; 12(1):32. Doi: 10.1186/s40345-024-00348-5. PMID: 39212809; PMCID: PMC11364728.

Could Lithium Explain — and Treat — Alzheimer’s disease? Study: Lithium loss ignites Alzheimer’s, but lithium compound can reverse disease in mice, 06 August 2025, Harvard Medical School, https://hms.harvard.edu/news/could-lithium-explain-treat-alzheimers-disease#:~:text=known%2C%20APOE

Shen Y, Zhao M, Zhao P, Meng L, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Taishi Y and Sun L (2024) Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential of lithium in Alzheimer’s disease: repurposing an old class of drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 15:1408462. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1408462

De-Paula VJR, Radanovic M, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: a review of molecular targets and biological effects at subtherapeutic concentrations in preclinical models of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2025 May 10;13(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s40345-025-00386-7. PMID: 40348943; PMCID: PMC12065699.